Session Group Encryption: Sealed Sender Without PFS Tradeoffs

Session trades Perfect Forward Secrecy for metadata minimization, routing encrypted messages through three-hop onion paths to protect sender and recipient identities from network observers.

Most messengers claiming "end-to-end encryption" focus obsessively on forward secrecy while leaking metadata to centralized servers that know exactly who talks to whom and when. Session flips this equation by hiding metadata through network architecture while making deliberate cryptographic tradeoffs that most privacy theater apps would never admit.

The Session Protocol routes every message through three randomly selected Service Nodes in the decentralized Oxen network, creating onion-encrypted paths where no single server knows both sender and recipient. Each of the three hops gets encrypted with the X25519 public key of its respective Service Node, meaning the first node knows your IP address but can only decrypt enough to learn the next hop's address, the middle node knows neither sender nor ultimate recipient, and the final node delivers the message without learning the sender's IP. This three-layer onion routing makes it cryptographically impossible for any individual server to map communication patterns across the network.

The sealed sender implementation uses libsodium's crypto_box_sealed() function, which creates ephemeral key pairs for each message and destroys the private key immediately after encryption. Standard sealed boxes provide recipient anonymity by preventing anyone intercepting the ciphertext from identifying who sent it, but Session adds an authentication layer by signing messages with the sender's ED25519 private key before sealing them. This hybrid approach means recipients can verify message integrity while network observers gain zero information about sender identity from examining encrypted traffic.

Group encryption uses the Sender Keys protocol, which generates a shared symmetric key SK when creating a closed group and distributes it through encrypted pairwise channels to each member. Groups support up to 100 participants, with all members using the same symmetric key to encrypt group messages rather than maintaining individual encryption sessions with each participant. When someone sends a group message, they sign it with their ED25519 private key, encrypt both message and signature using the group's shared key and the recipient's X25519 public key through crypto_box_sealed(), then broadcast the result to all group members through their respective swarms.

Message storage happens on swarms of 5-10 Service Nodes that map deterministically from recipient public keys, creating redundancy without requiring every node to store every message. Swarms replicate each message across multiple servers so that if individual nodes go offline, messages survive until recipients retrieve them. All stored messages carry a time-to-live (TTL) that triggers automatic deletion after expiration, meaning the network provides temporary message storage rather than permanent cloud backups. Messages remain encrypted on swarm servers using keys that exist only on recipient devices, preventing Service Node operators from accessing content even if they control entire swarms.

The Session Protocol deliberately omits Perfect Forward Secrecy in both one-to-one chats and closed groups, a tradeoff that most privacy-focused messengers would consider heretical. Traditional PFS implementations use ephemeral key ratcheting where each message uses a new encryption key that gets destroyed after use, ensuring that compromising a device today reveals zero information about messages sent yesterday. Session abandoned this approach when moving away from the Signal Protocol because maintaining PFS ratchets requires synchronization mechanisms that leak metadata about which devices belong to the same user and when they last synchronized.

The cryptographic foundation combines ED25519 for digital signatures and X25519 for encryption, using the same 32-byte seed to derive both keys deterministically. Account IDs come from the public ED25519 key, creating a verifiable link between account identity and signing authority without requiring phone numbers or email addresses for registration. Messages get signed with ED25519 to prove authenticity, then encrypted using X25519 Diffie-Hellman key agreement with the recipient's public key, combining authentication with confidentiality in a two-step process that separates identity from encryption.

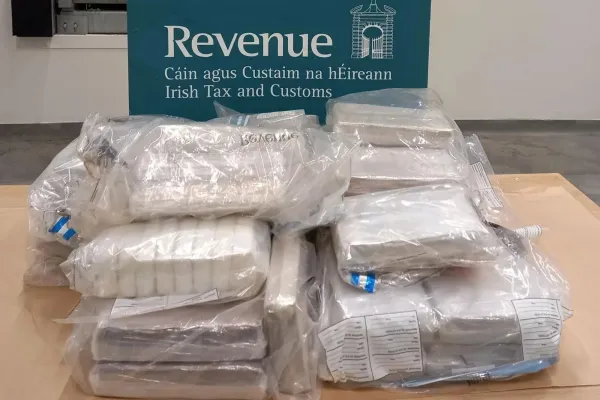

The Oxen Service Node network provides infrastructure through cryptocurrency-staked servers operated by users who lock collateral to participate, creating Sybil resistance through economic incentives rather than centralized access control. Service Nodes earn rewards for providing storage and bandwidth, but they can only decrypt the onion layer meant for them and gain zero access to message contents or comprehensive metadata about communication patterns. Running a Service Node requires staking 15,000 OXEN tokens, which creates a financial barrier against spinning up thousands of malicious nodes to execute traffic analysis attacks.

Account creation requires no phone number, email, or recovery questions, generating identity from a random keypair that users must back up manually if they want to recover their account after losing their device. This eliminates the metadata linkage that comes from phone number verification while shifting responsibility for key management entirely to users who might lose access permanently if they fail to record their recovery phrase. The protocol cannot implement password resets or account recovery assistance because no central authority maintains a database mapping accounts to real-world identities.

Session moves away from the Signal Protocol that it initially used, abandoning deniability and PFS in one-to-one chats to gain metadata minimization and multi-device synchronization without phone number linkage. The old approach provided mathematical guarantees that compromised long-term keys revealed nothing about past messages, but it required complex ratcheting state that made multi-device support nearly impossible without a central server coordinating which device received which messages. The new Session Protocol accepts that stealing someone's device grants access to all their message history while gaining the ability to sync across devices without creating a metadata trail linking those devices to a phone number.

Onion requests use existing X25519 keys held by each Service Node Storage Server rather than requiring separate keys for routing versus storage functionality. This simplification means the same cryptographic infrastructure handles both onion routing and final message delivery, reducing complexity while maintaining the core privacy property that no individual node learns both endpoints of communication. The onion system handles only TCP traffic suitable for asynchronous messaging rather than supporting UDP streams or exit node functionality that would enable real-time communication or general-purpose network tunneling.

The protocol makes explicit tradeoffs that prioritize metadata protection over cryptographic perfection, accepting known limitations in exchange for a threat model focused on network-level surveillance rather than device compromise. Organizations running mass surveillance infrastructure can observe IP addresses connecting to the Oxen network but cannot determine who communicates with whom or when without compromising multiple randomly-selected Service Nodes along specific routes. Adversaries who physically seize devices gain full access to message history because the protocol stores messages decrypted on local storage rather than maintaining them encrypted with ephemeral keys.

Session treats metadata protection as the primary security goal while acknowledging that device security falls entirely on users implementing their own operational security practices. The architecture assumes that government surveillance targets network traffic analysis rather than individual device compromise, making it more resistant to dragnet monitoring while remaining vulnerable to targeted attacks where adversaries gain physical or remote access to specific devices. This represents a fundamentally different security model than messengers optimizing for device compromise scenarios while routing all metadata through centralized servers that create comprehensive social graphs.