Domain Fronting: How Censors Killed Privacy on the Cloud

By putting one domain in the TLS handshake and another in the HTTP header, domain fronting made Signal unstoppable in Egypt, Oman, and UAE—until corporations caved to authoritarian pressure.

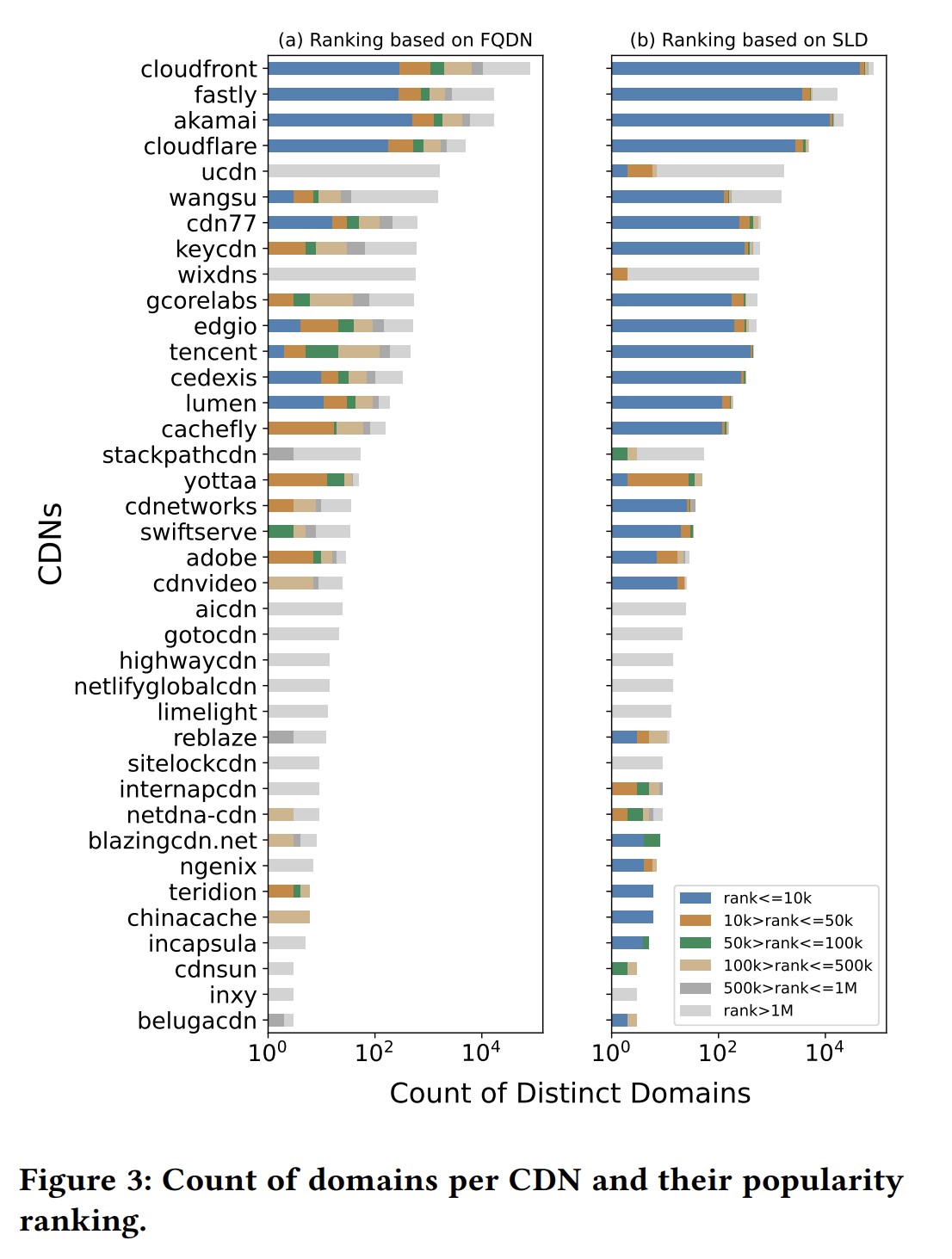

Domain fronting was the most elegant censorship circumvention technique ever deployed at scale. It exploited how content delivery networks route traffic, letting users in Egypt connect to Signal by making requests look like they were going to google.com. For a few years, it worked brilliantly. Then in April 2018, Google and Amazon simultaneously shut it down, and the technique that kept millions connected to encrypted messaging died overnight.

(members quiz at bottom)

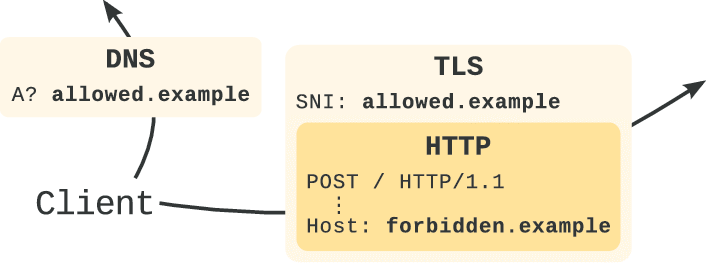

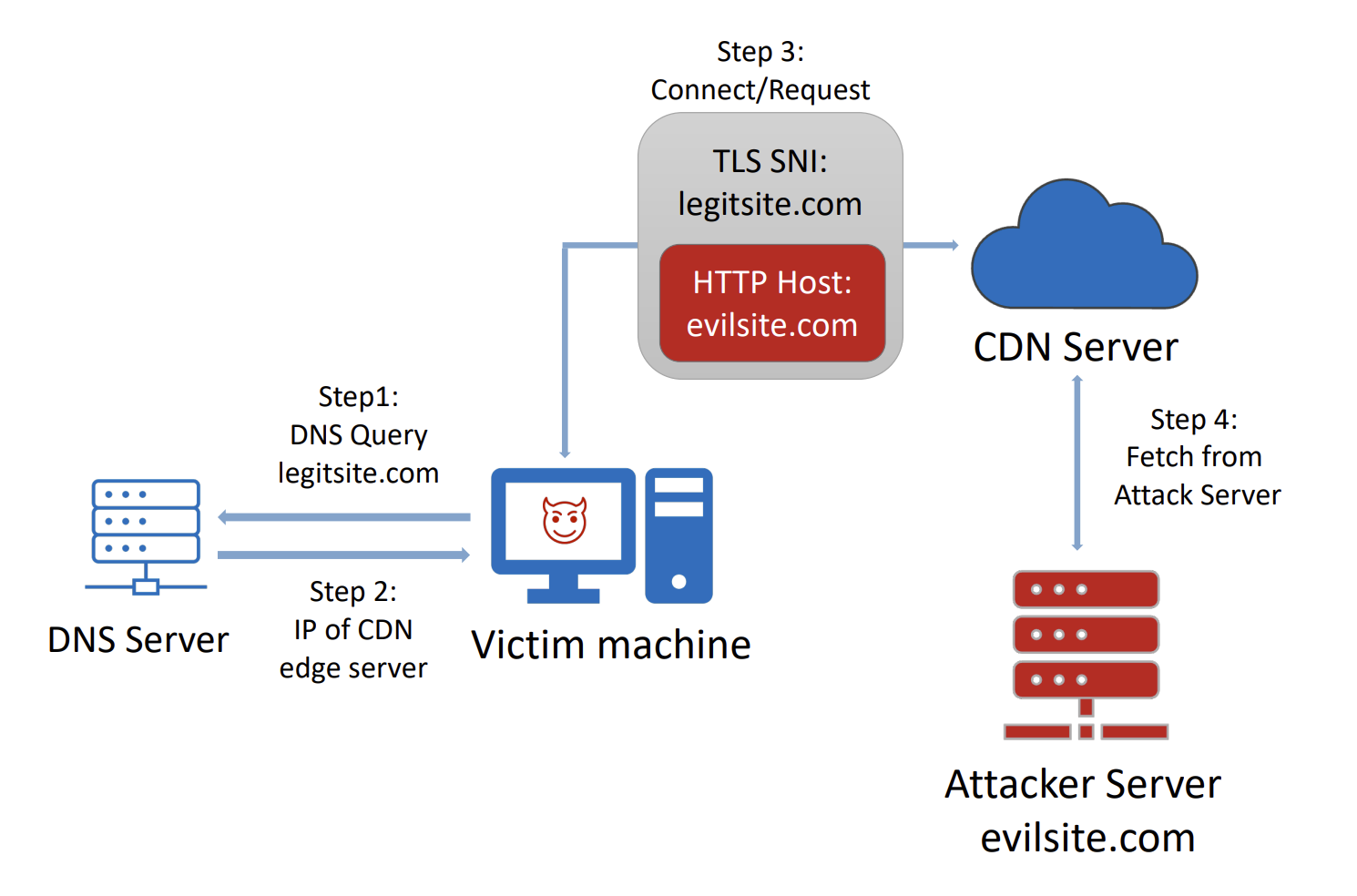

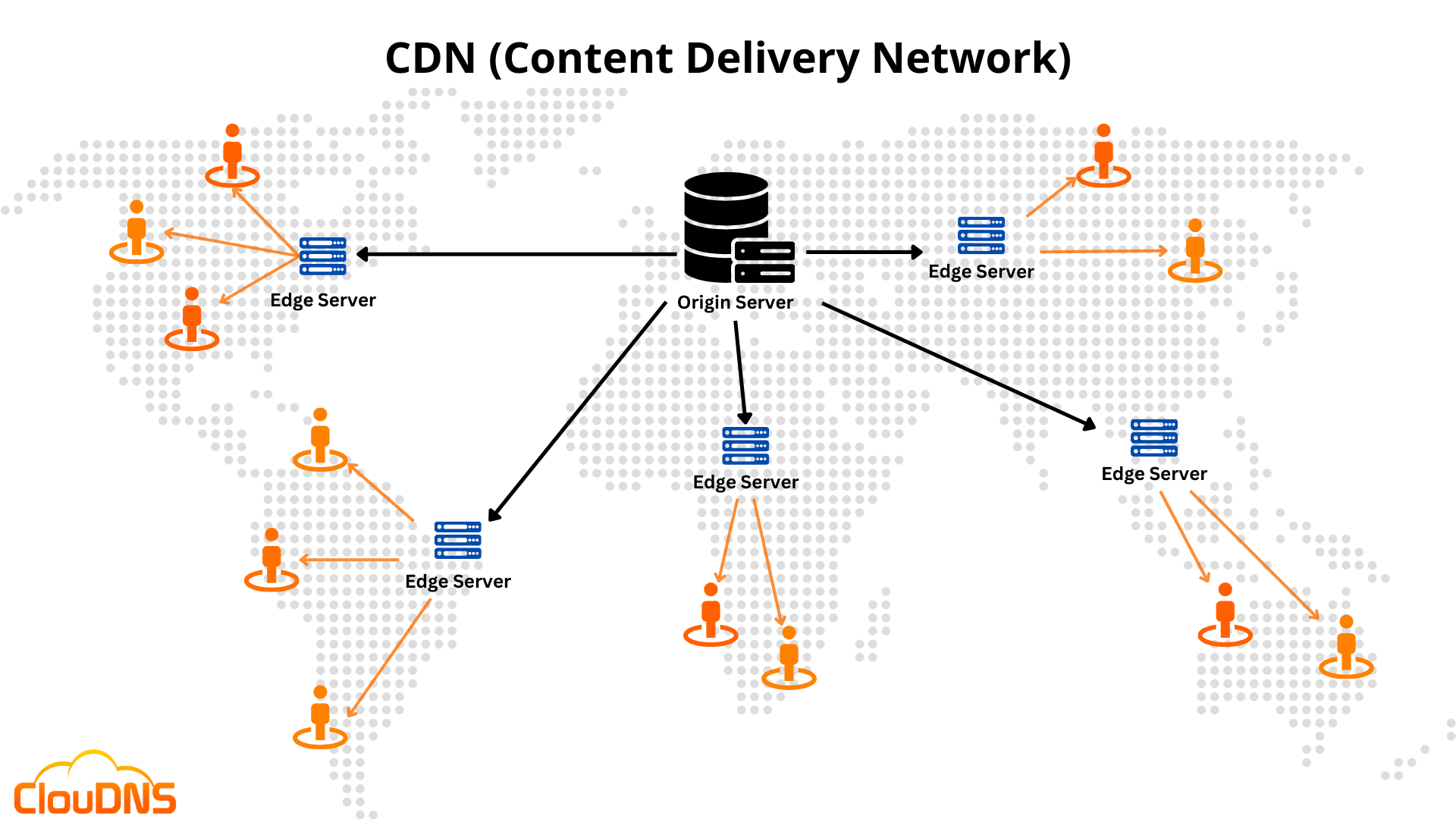

The technical mechanism was pretty simple. HTTPS connections contain two places where you specify the destination domain: the Server Name Indication (SNI) field in the TLS handshake, and the Host header in the HTTP request. Censors see the SNI field because it travels in plaintext during the initial connection. The Host header is encrypted inside the TLS tunnel, invisible to anyone monitoring the wire. Domain fronting exploited this gap by putting a benign domain in the SNI field and the real destination in the Host header. When both domains lived on the same CDN, the CDN would route the request to whichever domain appeared in the Host header, completely bypassing censorship filters watching only the SNI.

Signal deployed this in countries where the app was blocked Egypt, Oman, Qatar, UAE, and Iran. They put google.com or ajax.googleapis.com in the SNI field while routing the actual Signal traffic through Google App Engine. To block Signal, censors would have to block all of Google, a step even authoritarian governments hesitated to take. The technique was so effective that Telegram, Tor, Psiphon, and Lantern all adopted it.

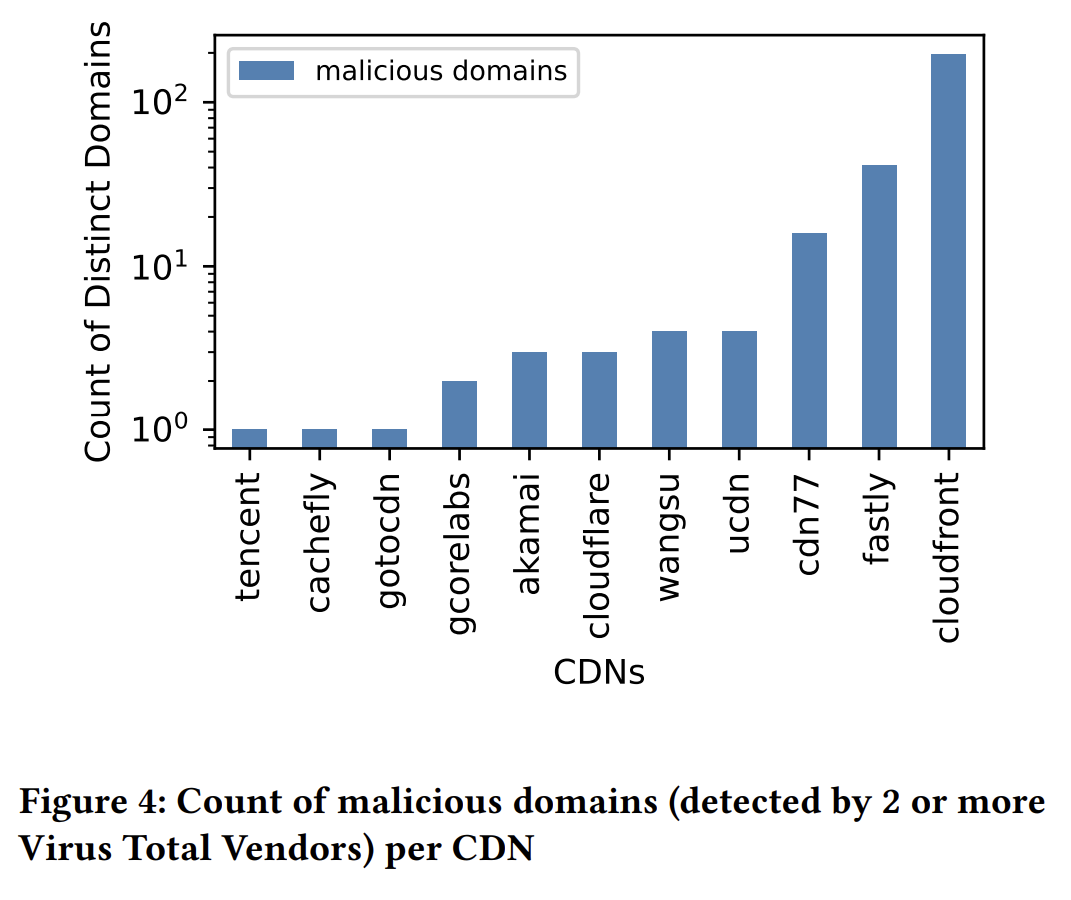

The problem was domain fronting worked too well. Malware authors noticed. APT29, the Russian state-sponsored group, used domain fronting with meek and Tor to hide command-and-control traffic. Cobalt Strike added domain fronting as a feature, letting red teamers and actual attackers hide C2 channels behind reputable domains. Zscaler documented how attackers used Azure CDN, Discord, and CloudFlare to serve malicious payloads while security tools saw only connections to trusted domains. The technique that helped journalists in Tehran also helped ransomware operators exfiltrate data from banks in New York.

Russia forced the issue. When Moscow ordered ISPs to block Telegram in April 2018 over the app's refusal to hand over encryption keys to the FSB, Telegram immediately pivoted to domain fronting using Google and Amazon infrastructure. Russia's telecom regulator Roskomnadzor responded by blocking 1.8 million IP addresses belonging to Google Cloud and AWS. The collateral damage was instant and widespread. Banking websites went offline. E-commerce platforms crashed. Mobile apps using Google or Amazon cloud services stopped working. The next day, Russia blocked another 14 million IPs, bringing the total to over 16 million addresses.

Telegram kept working.

The ban failed completely, but it demonstrated to Google and Amazon exactly how much pressure authoritarian governments were willing to apply.

Within days, Google pulled the plug. On April 14, 2018, Google silently killed domain fronting in Google App Engine. The official statement claimed domain fronting "had never been a supported feature" and that the change was just a "planned software update" separating previously linked IT resources. Signal's domain-fronted connections immediately stopped working. Tor developers confirmed on April 13 that Google App Engine no longer accepted domain-fronted requests. Privacy advocates were furious. Access Now's Peter Micek stated the decision would "levy immediate, adverse effects on human rights defenders, journalists, and others struggling to reach the open internet."

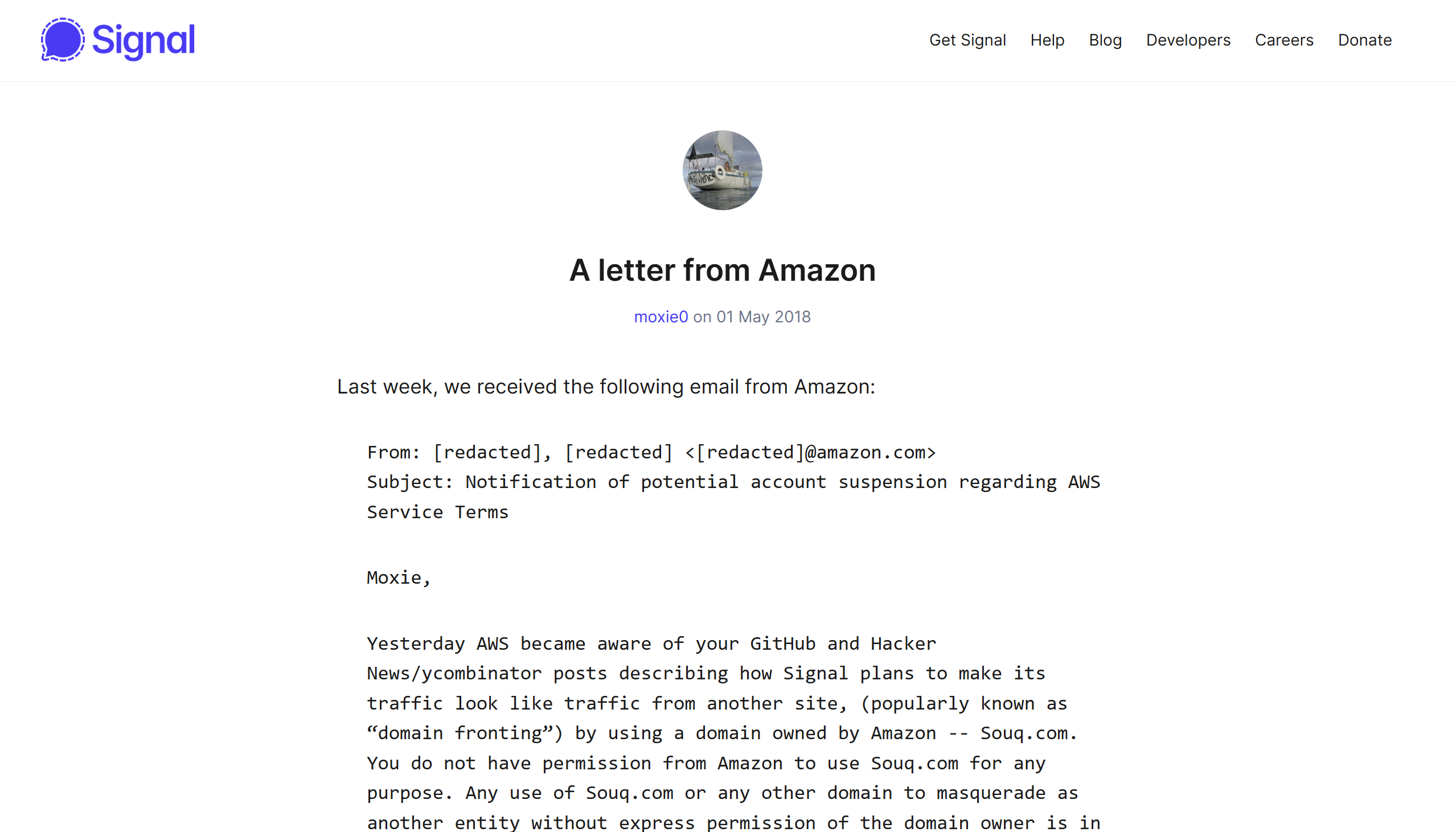

Amazon followed two weeks later. On April 27, Amazon announced CloudFront would no longer permit domain fronting, calling it a violation of AWS Terms of Service. Signal had already migrated to CloudFront after Google's ban, so this second shutdown permanently ended Signal's domain-fronted censorship bypass. The Tor Project scrambled to migrate to Microsoft Azure, which still permitted domain fronting at the time. But the writing was on the wall.

Senators Ron Wyden and Marco Rubio sent a rare bipartisan letter to Google and Amazon CEOs urging them to reconsider, citing harm to global internet freedom. The companies didn't budge. Their business calculus was clear: continuing to support domain fronting meant constant fights with Russia, China, and other censors willing to block millions of IPs and break unrelated services.

The technique that relied on CDN providers being unwilling to discriminate between customers only worked as long as the collateral damage of blocking was worse than the political cost of allowing circumvention. Once authoritarian governments proved they'd accept the collateral damage, then the leverage disappeared.

Signal acknowledged defeat with unusual candor. Their blog post stated censors had temporarily achieved their goals by waiting for cloud providers to eliminate domain fronting. The technique that made Signal unstoppable in Egypt was gone, and they had no immediate replacement. They mentioned working on "a more robust system" but admitted it would take time to develop. In the meantime, users in repressive countries lost access.

The technical details of why domain fronting worked reveal how fragile internet freedom infrastructure really is. During a TLS handshake, the client sends the SNI before encryption begins. This is necessary because servers hosting multiple domains need to know which TLS certificate to present. The Host header comes later, after the TLS tunnel is established and encrypted. CDNs historically routed traffic based on the Host header because that's the authoritative destination in HTTP semantics. Domain fronting exploited the fact that these two fields could contain different values, and CDNs prioritized the encrypted one.

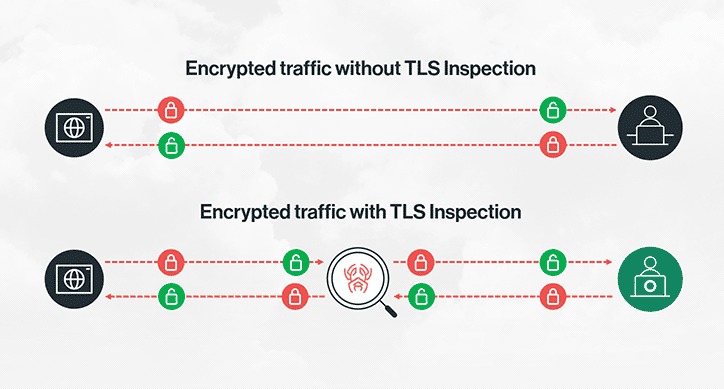

Detection requires SSL/TLS inspection, where a proxy terminates the TLS connection, examines the decrypted HTTP headers, and checks for SNI-Host mismatches. Most network firewalls don't do this because TLS inspection is expensive, breaks certificate pinning, and requires installing root certificates on every client. Authoritarian governments can mandate this for all traffic, but CDN providers had to choose whether to implement the check themselves. Google, Amazon, and eventually Microsoft decided they would.

Research published in 2024 found domain fronting still works on 22 out of 30 tested CDNs, including major providers like Akamai and Fastly. The technique isn't dead it's just locked out of the biggest platforms. Smaller CDNs either haven't implemented SNI-Host matching checks or don't face enough pressure from censors to bother. But without Google, Amazon, or Azure, domain fronting lost the key property that made it powerful: these were domains censors couldn't afford to block. Akamai and Fastly host major websites, but they're not google.com. The risk calculus for censors is different.

Microsoft eventually joined the ban. On January 8, 2024, Azure Front Door and Azure CDN began blocking requests with mismatched SNI and Host headers. The notice gave customers months to prepare, framing domain fronting as a security issue rather than acknowledging the censorship implications. Azure now only allows mismatched headers if both domains are registered to the same Azure subscription, which defeats the entire point of domain fronting for censorship circumvention.

CloudFlare banned domain fronting earlier than the others, in 2015, stating it would "put traditional customers at risk as it would mask banned traffic behind their domains." The company framed it as protecting their paying customers from being used as unwitting fronts. This was three years before the 2018 crackdown, suggesting CloudFlare saw the liability risk before Russia forced the issue.

The malware angle gave cloud providers political cover to kill domain fronting without admitting they were caving to authoritarian pressure. Google and Amazon both cited abuse concerns in their explanations, pointing to APT groups and ransomware using the technique for command-and-control. This framing ignored that the same technique protected journalists and activists, but it was more palatable than admitting they chose market access over human rights. Senators Wyden and Rubio's letter explicitly called out this dodge, but it didn't change the outcome.

From a technical standpoint, defenders have few options against domain fronting once it's in use. The only reliable detection is TLS inspection, which requires organizations to deploy HTTPS proxies with SSL termination. This means the proxy decrypts all traffic, inspects the HTTP headers, and re-encrypts it before forwarding. Enterprises can force this on employees by installing custom root certificates. Censors can mandate it at the ISP level. But it breaks certificate pinning, a security feature where apps refuse to accept any certificate other than the one they expect. Signal uses certificate pinning, so TLS inspection breaks Signal entirely which is exactly what some governments want.

The fact that domain fronting relied on a quirk in CDN behavior, not any protocol flaw, meant there was never a standards-based solution. The IETF couldn't fix this with an RFC because it wasn't a bug. CDN providers had to actively choose whether to compare the SNI and Host fields and block mismatches. For years, they chose not to, either because they didn't care or because they saw value in supporting censorship circumvention. When the political and legal pressure exceeded the reputational benefit, they flipped the switch.

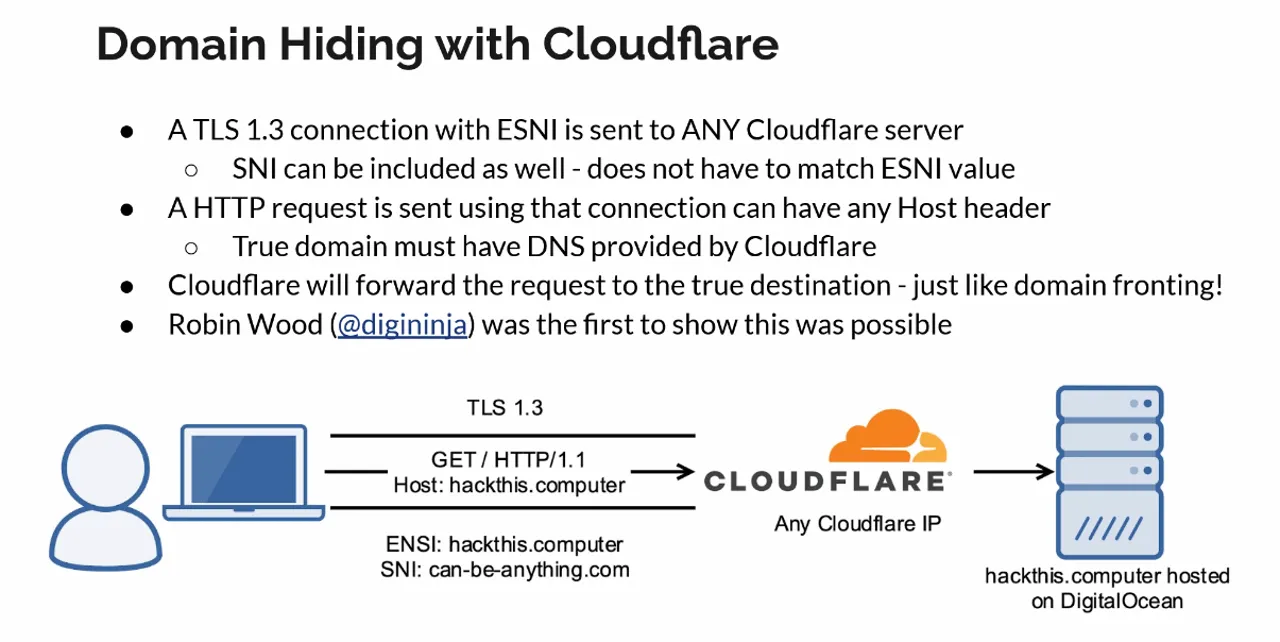

Newer techniques have emerged. Encrypted Client Hello (ECH), formerly known as Encrypted SNI (ESNI), encrypts the SNI field inside the TLS handshake, preventing censors from seeing the destination domain at all. This doesn't require CDN cooperation like domain fronting did, making it more robust against provider shutdowns. But ECH has its own problems. It requires both client and server support, deployment is slow, and some networks block it entirely precisely because it prevents SNI inspection. China's Great Firewall actively interferes with ECH.

Domain fronting also inspired "domain hiding," a variant where the SNI field is left blank or set to the IP address instead of containing a different domain. This works with some CDNs but is even easier to detect and block than standard domain fronting. The blank SNI immediately flags the request as suspicious.

The 2018 shutdown revealed how much of internet freedom infrastructure depends on the tolerance of a handful of American corporations. Signal, Tor, and Telegram didn't control the technique they relied on. They were borrowing infrastructure from companies that owed them nothing and could revoke access instantly. When Google and Amazon decided domain fronting was more trouble than it was worth, there was no appeal process, no negotiation, no fallback. The technique died because three companies changed their routing logic.

Privacy maximalists took the wrong lesson.

Many argued the bans proved you can't trust centralized services, which is true but misses the deeper point. Domain fronting worked because CDNs are centralized. The censorship bypass relied on the censor being unwilling to block google.com because too much other infrastructure depended on it. Decentralized systems don't have this property. There's no collateral damage to blocking a Tor exit node. The very centralization that made domain fronting powerful also made it fragile.

Russia's brute-force IP blocking, despite its failure to stop Telegram, demonstrated what happens when a government decides collateral damage is acceptable. Blocking 16 million IPs broke banking and e-commerce, but the Russian government didn't care. The political goal of silencing Telegram outweighed the economic disruption. If Google and Amazon had kept allowing domain fronting, the next escalation would have been blanket blocks of their entire IP ranges in multiple countries, forcing the companies to choose between specific markets and the censorship bypass feature.

The fundamental problem is that censorship circumvention tools can't rely on adversary mistakes. Domain fronting worked because censors weren't willing to block major CDNs. Once Russia proved they were willing, the technique's days were numbered. Any circumvention method that depends on the censor choosing not to use an available countermeasure isn't a solution it's borrowed time.

Today, domain fronting exists in a legal and technical gray zone. MITRE ATT&CK documents it as a command-and-control technique used by APT groups. Security vendors flag SNI-Host mismatches as indicators of compromise. The technique that helped activists in authoritarian countries is now primarily associated with malware. This reputational shift made it easier for cloud providers to ban without facing as much criticism from privacy advocates.

The 22 CDNs that still allow domain fronting in 2024 are mostly smaller providers without the political exposure of Google or Amazon. They face less pressure from governments and have fewer customers who might complain about being used as fronts. But they also lack the scale and ubiquity that made domain fronting effective. A censor can block a smaller CDN without breaking critical infrastructure. The technique still exists, but it lost the leverage that made it work.

Domain fronting's rise and fall maps directly to the power dynamics of the internet. For a brief period, the architecture of CDNs created an opportunity where the cost of blocking circumvention tools exceeded the cost of allowing them. Activists, privacy tools, and censorship circumvention projects exploited that window. Then malware authors did the same, censors escalated their blocking, and cloud providers closed the gap. The technique didn't fail technically it failed politically.

The lesson is that privacy and censorship resistance can't depend on infrastructure controlled by entities with conflicting incentives. Google and Amazon aren't human rights organizations. They're businesses subject to government pressure in every country where they operate. Expecting them to maintain features that antagonize authoritarian governments indefinitely was wishful thinking. Domain fronting worked until it became expensive, then it died. The next censorship bypass technique will follow the same arc unless it's designed not to depend on corporate tolerance.